The house (history)

Schoone Oordt is a historic home in the heart of Swellendam, with roots dating back to the early 1800s. Shaped by generations of families, the house has seen times of grandeur, decline and careful restoration, most notably in the late 1960s.

Recognised as a National Heritage Building in 1983, it remains a place where history is gently preserved and shared, with stories living quietly in every corner.

It was and continues to be quite a challenge correctly sourcing the history of this beautiful old house as the archives in both Cape Town and Swellendam have on separate occasions (obviously) been destroyed by fire. There are no plans, no official records and for the longest time, we published a ‘word of mouth’ story that we had collected from various people over time, beginning with the ownership of the Anderson sisters in 1853. This is when we believed the house was built, named Schoone Oordt and our logo reflects so.

That is, until Roger Lewis Aspeling came to stay with us in March of 2013. He mentioned that his great- great grandfather had owned this property way before that, he can’t quite pinpoint when the house was named either and has proceeded to embark on a massive historical project culminating in a draft manuscript sent to us in June of this year. He has attempted to reconstruct a timeline and piece together some history and until such time as we can officially publish his findings, here is a timeline taken from ‘Historical Houses in Swellendam: A pamphlet [sic] series for schools, published 2002 by M. v. Hemert….’

Short summary of owners:

- 1831 Johan Gustav Aspeling

- 1835 Dirk Jacobus Aspeling

- Catherina Helena Anderson

- 1840 – 1850 Frederik Blucher Scrutton

- 1853 Johannes Zacharias Human (double storey added)

- 1887 Part of the ground goes to the Kerkraad

- Lieberman & Buirski

- 1901 PC Muller

- AJ Barry

- WJ Odendaal

- Mev Maria Muller

- 1972 Santa & Fanie Hofmeyr

- 1980 Danie Theron

- 2003 Alison & Richard Walker

- 2007 Schoone Oordt Country House opens for business

This article written by Petra Gupta and published in the Sarie Marais magazine, 5th October 1977 pp 20 to 25 gives a beautifully written history up to the eccentric headmaster and his family, the Hofmeyrs. The writing on Dulcie Moore reflects Richard’s work and it’s sometimes spine-chilling how this grand old house captures and binds emotions. The article is in Afrikaans but has been translated into English by Maureen Rall.

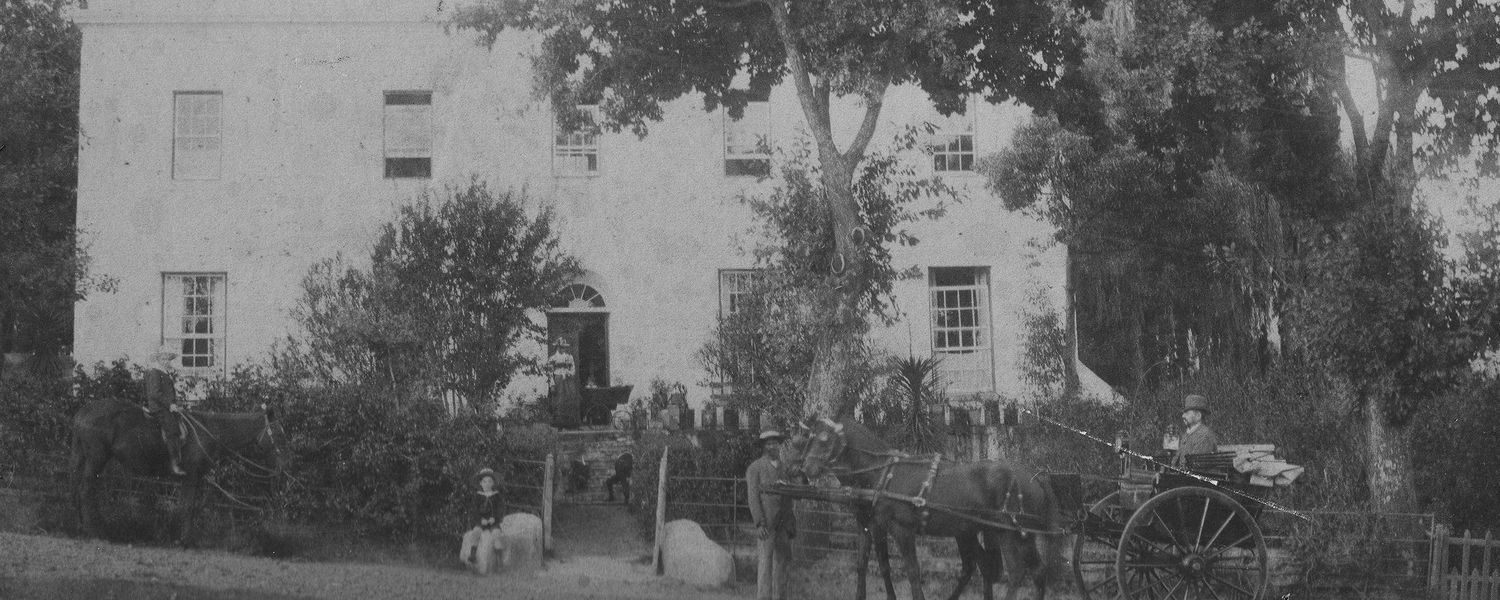

‘From the earliest history of the town a low Cape-Dutch dwelling had stood on this erf, probably built as an outbuilding to Morgenzon next to it, the oldest official building on this side of the river, as was the Drostdy on the other side. The present house was built on to and over the old building. Invisible from the front there extends at the back another part of a house where the thick outer walls and handmade metal cramp-irons attest to old workmanship. Little has as yet been written about this old section. It is likely that the Johannes Aspeling to whom the Landdrost and Heemraden allotted the erf in 1831 lived there. A recently discovered photograph of Swellendam, taken before the great fire of 1885 destroyed forty houses in the centre of town, shows such a low dwelling with a thatched roof among the riverine trees.

The house became immediately prominent with its first eminent occupant – Zacharias Human, member of the Volksraad and town benefactor, who when the whole of Swellendam had recovered from the fright of the huge mountain fire, had himself, like many other people in the town, a huge square double-storey house built in the English Georgian style with a flat roof.

We who are accustomed to modern squareness can hardly imagine what impression this important building made in a town with its rounded dark thatched roofs grazing like a flock of peaceful sheep next to water. Such a house shows everything that it has in front. It brings the first balconies to the town. It is the home of a man who thinks himself of importance. And this was Zacharias. He lived there in great style, initially with his first wife who was twenty-one years older than himself and then – take notice! – with the housekeeper of Skone Oord whom he married shortly after his first wife’s death. He lies buried in a marble tomb next to the large church, just down the road.

The next occupants were a generation of well-known Jewish merchants – the Buirski’s, partner in the firm Lieberman and Buirski of Swellendam, big buyers of wool and wheat. Abraham Buirski raised a large brood of children here. Presumably, it was he who had the Victorian verandas and wrought iron additions installed on the flat façade of Zacharias’ Georgian construction.

During this century [twentieth] the house became the property of the Muller family, then of the families Barry, Odendaal and again Muller. Thereafter it was uninhabited and became dilapidated and spooky with damp walls, warped floorboards and shutters hanging askew. It was no longer ‘Skoon’ [beautiful] in any sense of the word. During its time the dwelling was known as the merriest place to visit in town. The elderly recount the dances and parties held there. It was a meeting place where the old wagon crossed the river. But now it had become a ramshackle building, although still an important one. While everywhere in town people restored and reappraised their Old Cape houses, experts began wondering what would happen to this hopelessly unmanageable space.

The restoration of the massive building was undertaken by a diminutive woman with a passion to succeed. Not born at Swellendam, and also no longer residing there because a tragedy took her away from the work of love which had occupied years of her life. Today Dulcie Moore lives in Pinelands, Cape Town, with her children. When Herman Moore, insurance agent, and she were transferred to Swellendam, they travelled there to look for accommodation and then discovered the derelict Skone Oord. They pushed open doors and braved the spiderwebs inside. It was pitch dark, a shelter for bats and creepy-crawlies, but when Dulcie and Herman emerged with spiderwebs across their faces, the house had bound them with much stronger ties. They promptly bought it, for little money. Then restoration started.

Work was started in July 1968. Three months after starting the first builder left. Defeated by the house. When the second builder also capitulated, Herman began to have doubts. We will never finish this task, he said. Then Dulcie tackled it herself. I shall do it, she said, and when I am finished, I’ll invite you to come and see. Herman kept his word. In the following eighteen months, while Dulcie struggled with the house every hour of the day (sometimes twelve of them) he paid and kept accounts but did not go to view it – until she was finished. Nobody in the town thought she would succeed. The further she advanced, the more the house showed its dilapidation. First the plaster work inside and outside was removed and plastered over. Then the floors (mostly of rotten yellow-wood) were lifted and replaced. All the doors and window frames were cleaned, renovated and replaced. The roof of the second storey was replaced. The endless wooden partitions above taken down and rebuilt (and rebuilt again – Dulcie did not shirk a thing!). At last the upper roof was also replaced.

The projects outside are prosaically recorded in the manifest: digging a drainage-channel, new stoep, kitchen chimney repaired, stone wall, wooden gate and small bridge, wall for railings, railings themselves. Concrete supports, furrows, dam… because such a house is an integral whole with its surroundings. Everything must look right, otherwise the restoration is faulty… and of course, the whole town is looking.

One day Dulcie’s workers even disappeared, so that she literally drove down the main street in her Volksie [Volkswagen] on the Monday morning and put everyone looking vaguely like a carpenter into it to deliver them at Skone Oord. She personally worked with her workers, passed bricks, battled with the trowel, carted things and encouraged, scrambled across the roof like a cat to loosen screws and throw down sheets of galvanised iron, later had every piece of metalwork taken off, dipped in hydrochloric acid by hand and scrubbed them clean, put them back… ‘And not once was I tired at night’, she says. She was deliriously happy and she could continue like this. It was her first restoration; she wishes she could tackle something like this again tomorrow.

The restoration cost them five, six times the price of the house. Meanwhile they started collecting old furniture so that when they moved in one day in February 1970, the place could be furnished in style. Then the cupboards and new stairway and bathrooms still had to be completed. Outside Dulcie laid out the giant lawn – with a pipe-line from the upper water furrow. It was laid down in November, scorching heat, and it was her work or a few days to move the pipe every half hour to prevent the cuttings from shrivelling up.

The Moores had not even been in the house for two full years when Herman became seriously ill. To be close to doctors they moved to Cape Town and offered Skone Oord for sale. Shortly afterwards, he passed on. ‘No’, said Dulcie, ‘I was sorry to leave there, but I was also satisfied. One always says: One day I am going to do this or that. I am going on a world tour or restore a house. Skone Oord was my one day: I am not asking for anything more.’

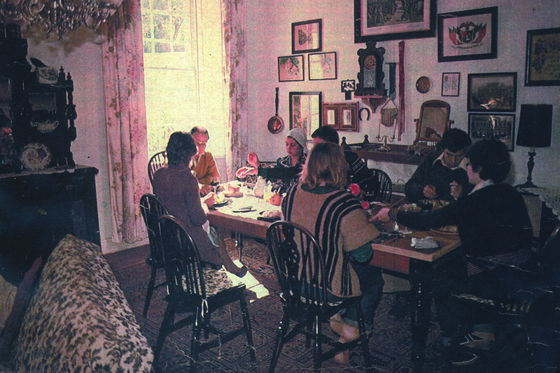

Santa and Fanie Hofmeyr who bought the house and passionately live in it, hail from the far Free State. They met in Bloemfontein and were married there. He is a historian and collects everything antique: furniture, timber, doors, window frames, beams, screws, you name it. At all the places where he had been a teacher and school principal, he collected things. At the time when he came to Swellendam as principal, there was already enough furniture for a large house.

As one listens to the story one begins to believe that it’s true that everything belonging to each other will inevitably come together. They HAD to have a large house. Santa loved Skone Oord from the day that she saw it. When they returned from a year’s visit abroad the house was standing empty – and was for sale. They bought it with light fittings and curtains as it stood. The furniture from the four corners of the country each found its own place and today the Hofmeyrs, their two daughters, the six (sometimes twelve) Chihuahuas, the four lambs, five geese and bantams belong to the large erf as though they had arrived there one by one a long time ago.

Most of the rooms of Skone Oord could easily swallow four modern rooms. The erf is four times the size of ordinary erfs. It stretches from the hillside to down below in the river, from hard loamy soil to the sweetest, dark river soil. On the erf, besides the imposing Manor House, many things are happening. Visiting the back one arrives at the coach-house. Once upon a time there must have been a major shodding centre for horses. From the soil armfuls of horseshoes emerge and everywhere on the twelve oak trees there are hooks to have tied them to. In the back Fanie Hofmeyr has a thriving farm on the go between the guava, plum, loquat and lemon trees that remain of the old orchard. Here he grows the finest vegetables and waits for his young vineyard to reach maturity. Down towards the river are the remains of an early bakery in Swellendam, where Dulcie had discovered the tumbledown oven. In the front garden pink roses still twine round the small bridge and violets flourish in the wet soil – because the whole erf is surrounded by furrows. Until recently Santa was in business. She managed an Old Cape restaurant in town. In those days the large house was empty during the day as the two daughters had already left school. Fanie was at the high school during the day.

She has subsequently not yet experienced the full joy of her new home. Now, since she has sold her restaurant she intends to plan the front garden anew and to research the history of the house properly. She says that it is an easy place to maintain and keep clean. With the help of Sarie Hartnick she manages quite well. In any case, her possessions are not a burden to her.

Skone Oord has a long history of hospitality. She enjoys having real people in the large rooms. Fanie looks after the outside. He is a tireless builder, creator and carpenter. One finds him down in the well-equipped (and also restored) cellar where he records the manifest of their work along the notices of the carpenter of 1885 where he left his measurements and preliminary sketches on the beams.

On the small square where Skone Oord is located one realises that you are here at the heart of the old town. Between the modest Cape-Dutch homes Skone Oord stands out as the crown piece, an embellishment worthy of its name.

One tries to imagine what the place would have looked like if the house had not been there. It is, and remains, unimaginable.

[Petra Greutter, Sarie Marais, 5 October 1977, pp. 20-25]

Fanie passed away unexpectedly 8 years after the Hofmeyr’s bought Schoone Oordt and the house became too large and difficult for Santa to manage on her own. She moved to Cape Town and Danie & Mercia Theron (the chemist and his wife) bought the house. They lived here very happily for twenty years with a houseful of children. Schoone Oordt was registered as a National Heritage Building in 1983 whilst the Therons owned it. Once the children had left home, the house once again became too big for Danie & Mercia to manage on their own. They sold to Richard and Alison Walker, the present owners, in 2003.

Share This Page